Rabbi Walter Plaut and the 1961 Freedom Ride

“I have learned that human suffering is indivisible”

On Tuesday, June 13, 1961 Rabbi Walter Plaut of Temple Emanuel in Great Neck, New York, was one of 18 clergymen on board the 11:15 a.m. Miami express bus leaving the Greyhound terminal in Washington, D.C. The men—7 Black and 7 white Protestant ministers and 4 white rabbis—embarked on the two-day Interfaith Freedom Ride to Tallahassee, Florida. Their mission was to protest racial segregation in bus terminals along the way. In 1960, the Supreme Court ruling Boynton v. Virginia banned segregation in the interstate passenger transportation industry after the Black law student Bruce Boynton had been denied service in a “whites only” restaurant in a Trailways terminal. The case was argued by Thurgood Marshall, who in 1967 became the first African American judge appointed to the Supreme Court.

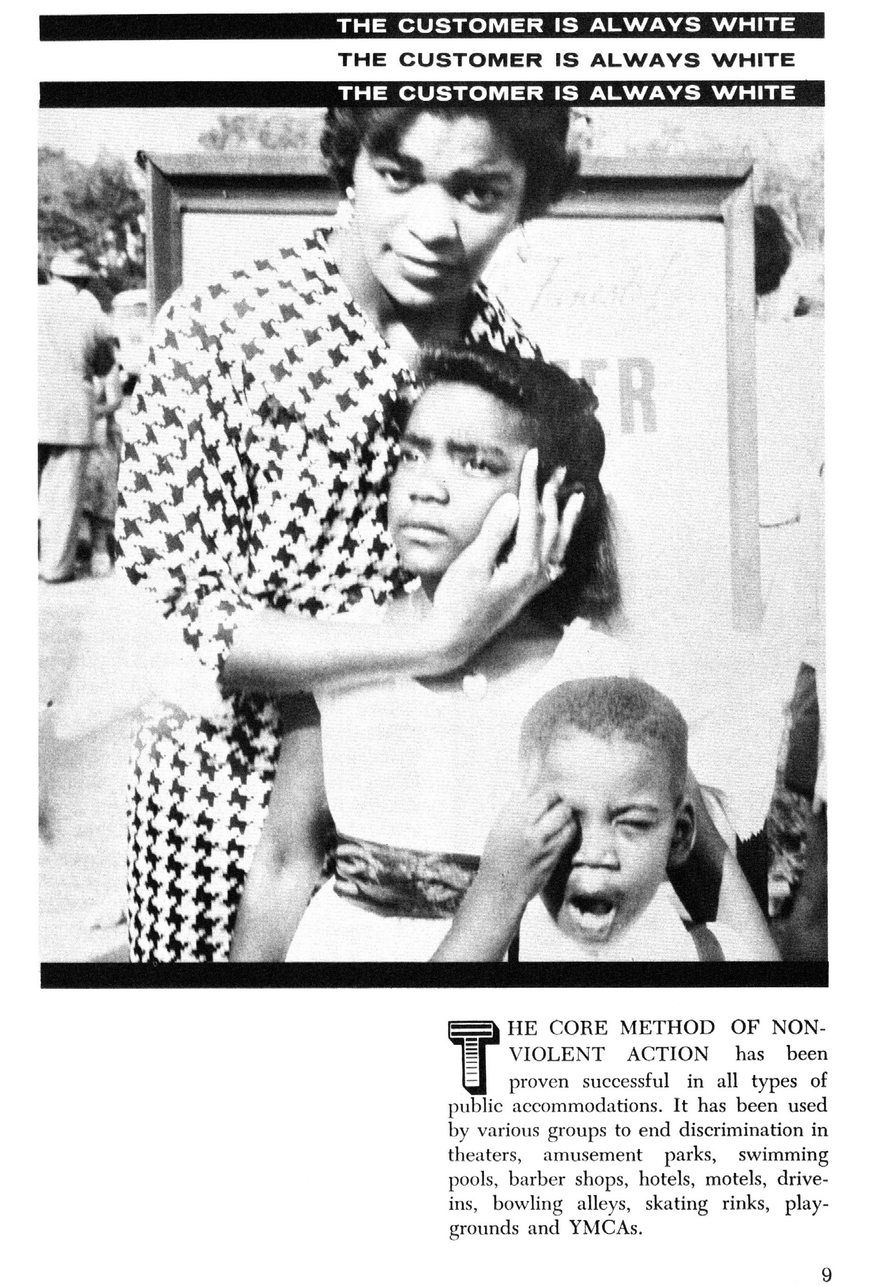

Despite the ruling, discrimination against Black customers was still enforced violently by civilians and police in many bus station facilities in Southern states. To transform the anti-segregation law into practice, the Freedom Riders’ strategy was to eat in restaurants and use restrooms and waiting areas in the bus terminals together in small groups of Black and white participants. The Interfaith Freedom Ride was sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who had also educated the participants in non-violent anti-racist activism.

Rabbi Walter Plaut’s participation in the Interfaith Freedom Ride is documented in his scrapbook in the digitized archival collections of the Leo Baeck Institute. A newspaper clipping in the collection shows that the Freedom Ride was not his first action against racial segregation: In 1940, Walter Plaut headed the Cincinnati Greater Racial Amity Committee while he attended Hebrew Union College. One action the group took was to integrate movie theaters. By 1961, he saw his anti-racist activism as an integral part of his duties as a rabbi. “Bridging the gap between word and action is always difficult. But I have a position of leadership and leadership means you must demonstrate your beliefs by example,” Rabbi Plaut explained to the press. He himself had arrived in the United States in August 1937 at the age of 18 after escaping the Nazis in Germany. His own experiences of persecution influenced the motivations for his participation in the Freedom Ride: “(…) I have witnessed at first hand the Holocaust of European Jewry. My immediate family was saved, but the rest of the far-flung family was murdered by the Nazis. I have learned that human suffering is indivisible and therefore I have special sympathy for the plight of the Negroes in the South.”

One of his fellow travelers on the Interfaith Ride, Rev. Arthur L. Hardge, a pastor of the Union African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church New Britain, Ct., commented: “Even with these specific instances of persecution, there is an overall feeling on the part of these ministers and rabbis that any persecution of minority groups jeopardizes the total civilization. Had this been a struggle against antisemitism instead of a struggle to secure the rights of Negroes, I am sure we would have joined them as fervently as they joined us.”

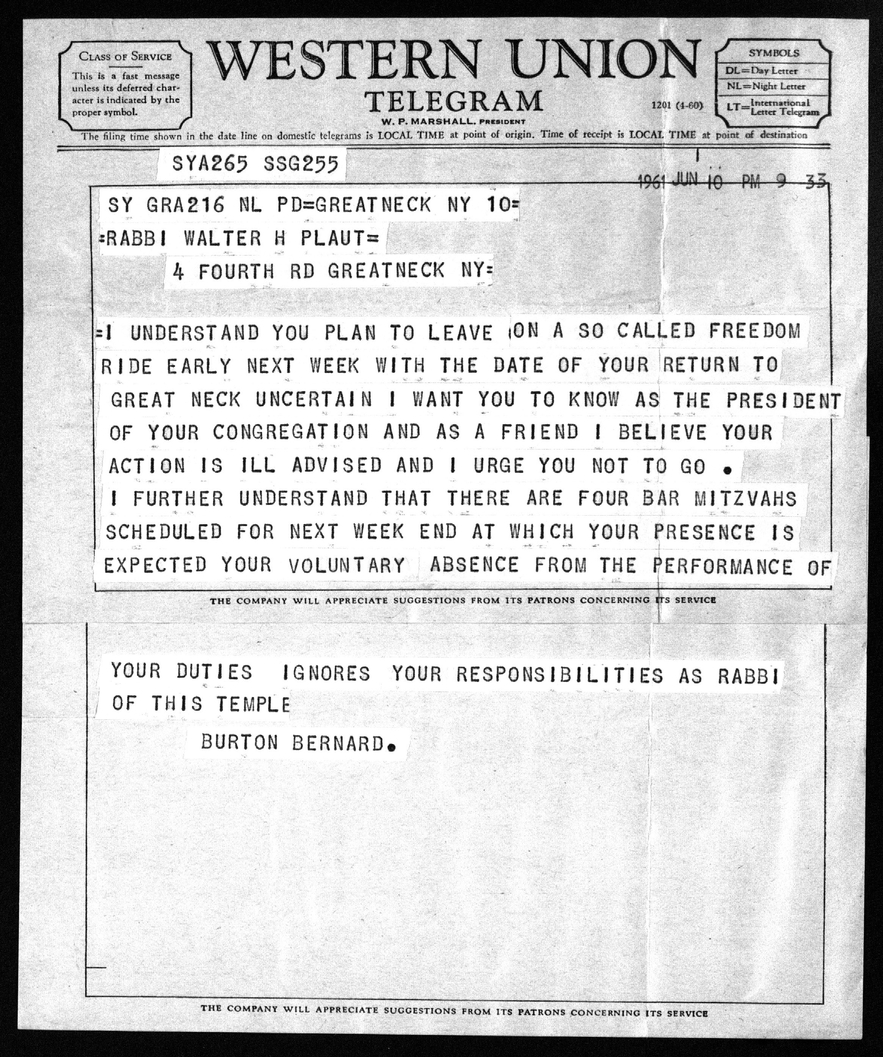

However, several members of Rabbi Plaut’s congregation in Great Neck did not support his decision to join the Freedom Ride. Three days before he left, Rabbi Plaut received a telegram from the President of his Temple that urged him to cancel his participation:

Despite this urging, Rabbi Plaut joined the bus trip to the South. The participants were aware of the dangers they could encounter along their way. A month before, many of the first Freedom Riders had suffered state and civil violence. Activists were arrested while disobeying segregation and brutally attacked by mobs of white supremacists that were partly supported by the police. In Anniston, Alabama, a firebomb was thrown into the bus while the passengers were on board, and in Birmingham, the passengers were viciously beaten by a crowd of white supremacists. Numerous activists were heavily injured.

On the first day of their trip the Interfaith Freedom Riders stopped in Richmond, Virginia, and later reached their destination in Raleigh, North Carolina. As the facilities in both stops were already desegregated, the group used the opportunity to rehearse their strategies for the stations in the Deep South where they expected resistance. The bus made one extra stop in South Hill, Virginia, where the driver was delivering a cargo package. After they saw a “whites only” sign installed at the station, the clergymen left the bus. Some of them almost got left behind as the driver then pulled away without waiting for all to return. After the incident, members of the group expressed concerns to the press about the Greyhound company trying to undercut their mission. Once in Raleigh, the Freedom Riders stayed overnight at the campus of the historically Black Shaw University, where the Civil Rights organization Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had been founded in April 1940.

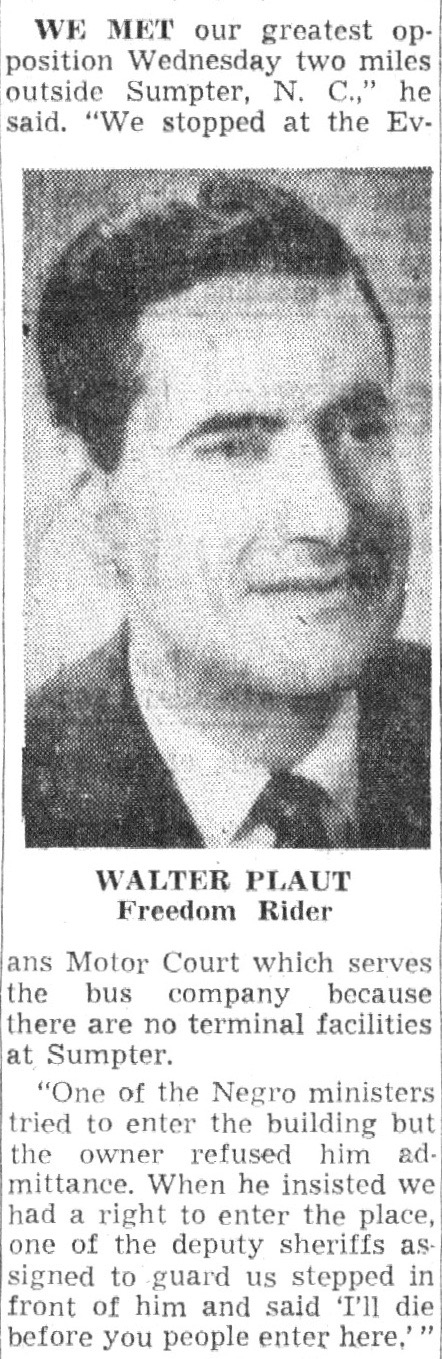

On the second day of their trip, the group traveled to Sumter, South Carolina. As the terminal did not provide dining facilities, passengers usually ate at the Evans Motor Court just outside of the city. When the clergymen wanted to enter the lunchroom there, they were stopped by a mob of 20 to 30 civilians as well as the local sheriff and his deputies. Rabbi Walter Plaut’s statement about the incident appeared in the Long Island Press:

The group was then informed that the facility had no affiliation with the Greyhound company and was therefore not an interstate transportation business bound to the Supreme Court decision. After a debate among the Interfaith Freedom Riders over whether to continue their protest, a group decided to get back on the bus to resume the ride, leaving those who had insisted on staying in Sumter displeased. Subsequently, they were welcomed with a religious service by the community of a Black church that had already hosted CORE-Freedom Riders in May. In the late evening they continued their way to Florida and during a stop in Jacksonville met a group of five activists of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for breakfast.

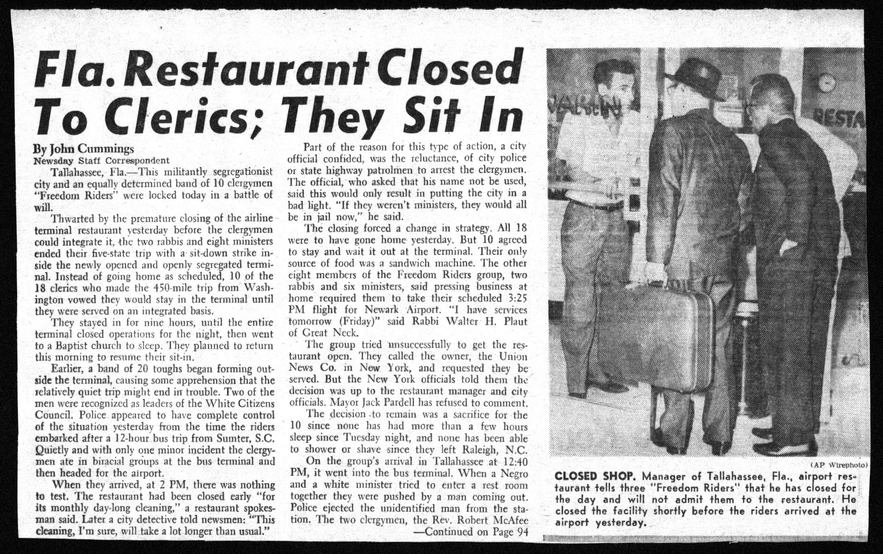

Finally, on June 15, the Interfaith Freedom Riders arrived at their last stop in Tallahassee. In the Trailways terminal, they encountered a crowd of aggressive civilians, and two Freedom Riders were pushed out of the restrooms by two white men. After a discussion with the police, they were able to use the restrooms during a second attempt. From there, the group went to the airport to fly back home, but before leaving, they planned to have dinner together. After passing about 20 opponents waiting outside the terminal, two of whom were identified as leaders of the white supremacist White Citizens Council, the Freedom Riders found that the airport’s restaurant had closed as soon as the they arrived. Rabbi Walter Plaut and seven other clergymen then took their flights back to attend scheduled events in their congregations.

The ten other activists decided to stay in Tallahassee as long as it would take the restaurant to open and serve them. After waiting for nine hours until the airport closed, they resumed their attempt to dine the next morning.

Joined by local activists and surrounded by police they waited in the terminal for five hours while in the background Florida’s governor C. Farris Bryant monitored the situation and even called U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to ask for help. The Freedom Riders were given an ultimatum to leave; when they didn’t comply, they were arrested and brought to city jail. They were released on bond the next day. Their trials lasted for three years and resulted in convictions. One of the clergymen paid a fine and the other nine served brief jail terms in August 1964.

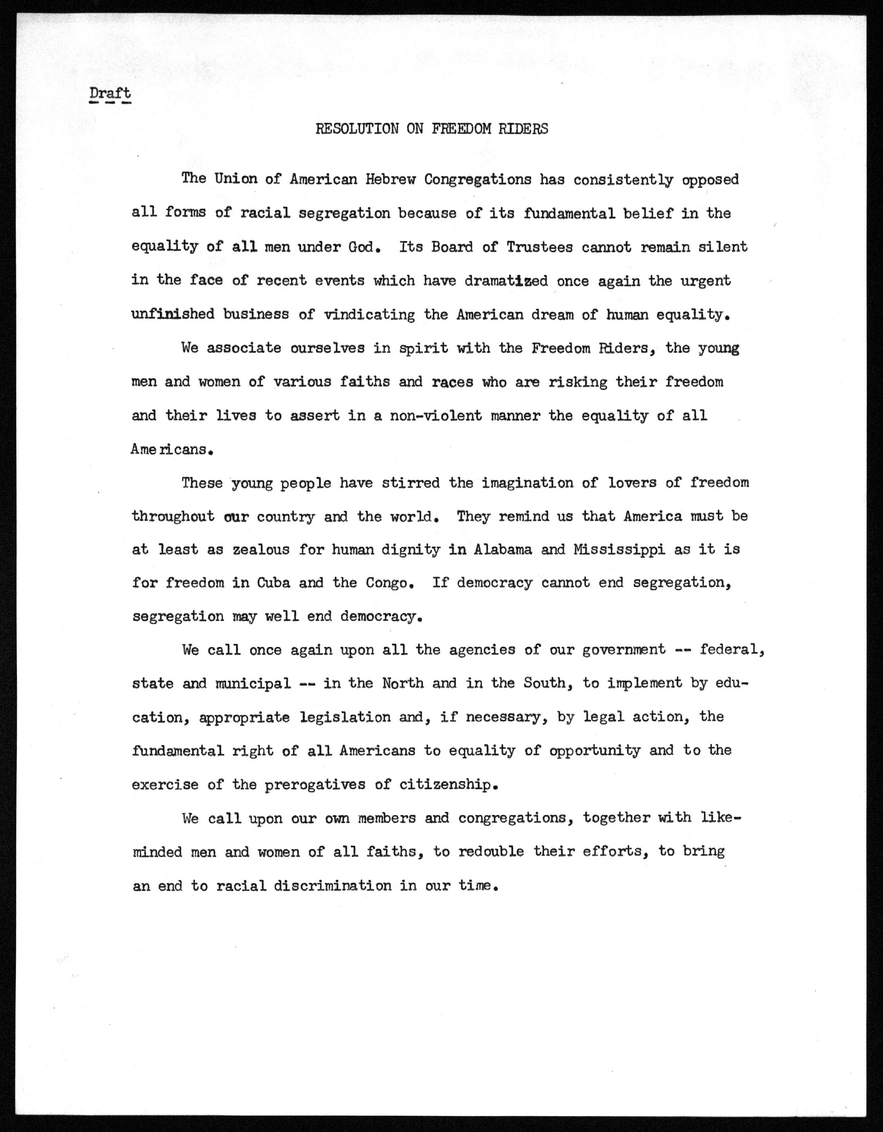

The participation of the rabbis in the Interfaith Freedom Ride was welcomed by many representatives of Jewish Organizations such as the Union of American Hebrew Organizations whose draft for a statement on the Freedom Rides was preserved by Walter Plaut in his scrapbook:

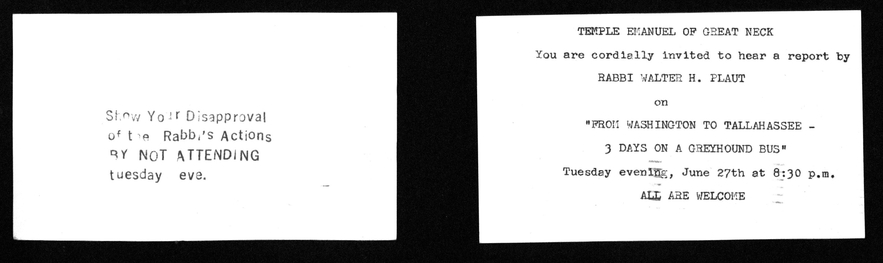

After his return, Rabbi Walter Plaut invited the public in Great Neck to an event in which he would report on his experiences on the Interfaith Freedom Ride. Again, he faced disapproval from some members of his congregation for his engagement in the cause of Civil Rights. A leaflet in response to the invitation urged people to stay away from the talk:

The divide in Rabbi Plaut’s congregation over his involvement in the Freedom Ride was severe and hurt him deeply. Still, he decided to convey a hopeful message upon his return and told the press that “within the foreseeable future this problem (segregation) will be virtually non-existent.”

Unfortunately, Rabbi Walter Plaut had too little time to contribute further to the abolition of segregation. Plaut, who had already been ill at the time he joined the Freedom Ride, died from cancer at the age of 44 on January 3, 1964, six months before the Civil Rights Act marked an important step for the cause to which he had devoted himself.

The participants in the Interfaith Freedom Ride were:

C. Donald Alstork, Minister, Dyer Phelps AME Zion Church (Saratoga, NY)

Robert McAfee Brown, Minister and Theologian (New York, NY)

John W.P. Collier, Minister, Israel Memorial AME Church (Newark, NJ)

Israel Dresner, Rabbi, Temple Sharey Shalom (Springfield, NJ)

Malcolm Evans, Minister, Church of the Crossroads (Brooklyn, NY)

Martin Freedman, Rabbi, Congregation B’nai Jeshurun (Paterson, NJ)

Arthur L. Hardge, Minister, Union AME Zion (New Britain, CT)

Wayne “Chris” Clyde Hartmire, Jr., Minister, East Harlem Protestant Parish (New York, NY)

George J. Leake, Minister, Durham AME Zion Church (Buffalo, NY)

Allan Levine, Rabbi, Temple Beth-El (Bradford, PA)

Petty McKinney, Minister, Eliza Ann Gardner AME Zion Church (Springfield, MA)

Walter Plaut, Rabbi, Temple Emanuel of Great Neck (Great Neck, NY)

Henry Proctor, Minister, AME Zion Church (Syracuse, NY)

Ralph Lord Roy, Minister, Grace Methodist Church (New York, NY)

Literature:

Plaut, Joshua Eli, My Father’s Journey on a Freedom Ride Bus, ReformJudaism.org, 2016, written by Rabbi Walter Plaut’s son who donated the scrapbook to the Leo Baeck Institute.

Arsenault, Raymond, Freedom riders: 1961 and the struggle for racial justice. Oxford University Press, 2006. (Chapter 8 provides a detailed account of the Interfaith Freedom Ride.)