The Leo Baeck Institute New York | Berlin would like to thank the following Cooperating Partners who contributed valuable resources to the production and maintenance of the 1938 Projekt:

The following organizations have offered their materials for inclusion in the 1938 Projekt:

BACK TO TIMELINE

ON THIS DAY

Sign up for weekly updates:

Success

Thank you for signing up.

Error

You're already a list member.

Error

An error occurred, please try again later.

The Leo Baeck Institute New York | Berlin would like to thank the following Cooperating Partners who contributed valuable resources to the production and maintenance of the 1938 Projekt:

The following organizations have offered their materials for inclusion in the 1938 Projekt:

The Leo Baeck Institute New York | Berlin would like to thank the following Cooperating Partners who contributed valuable resources to the production and maintenance of the 1938 Projekt:

The following organizations have offered their materials for inclusion in the 1938 Projekt:

Sign up for weekly updates:

Success

Thank you for signing up.

Error

You're already a list member.

Error

An error occurred, please try again later.

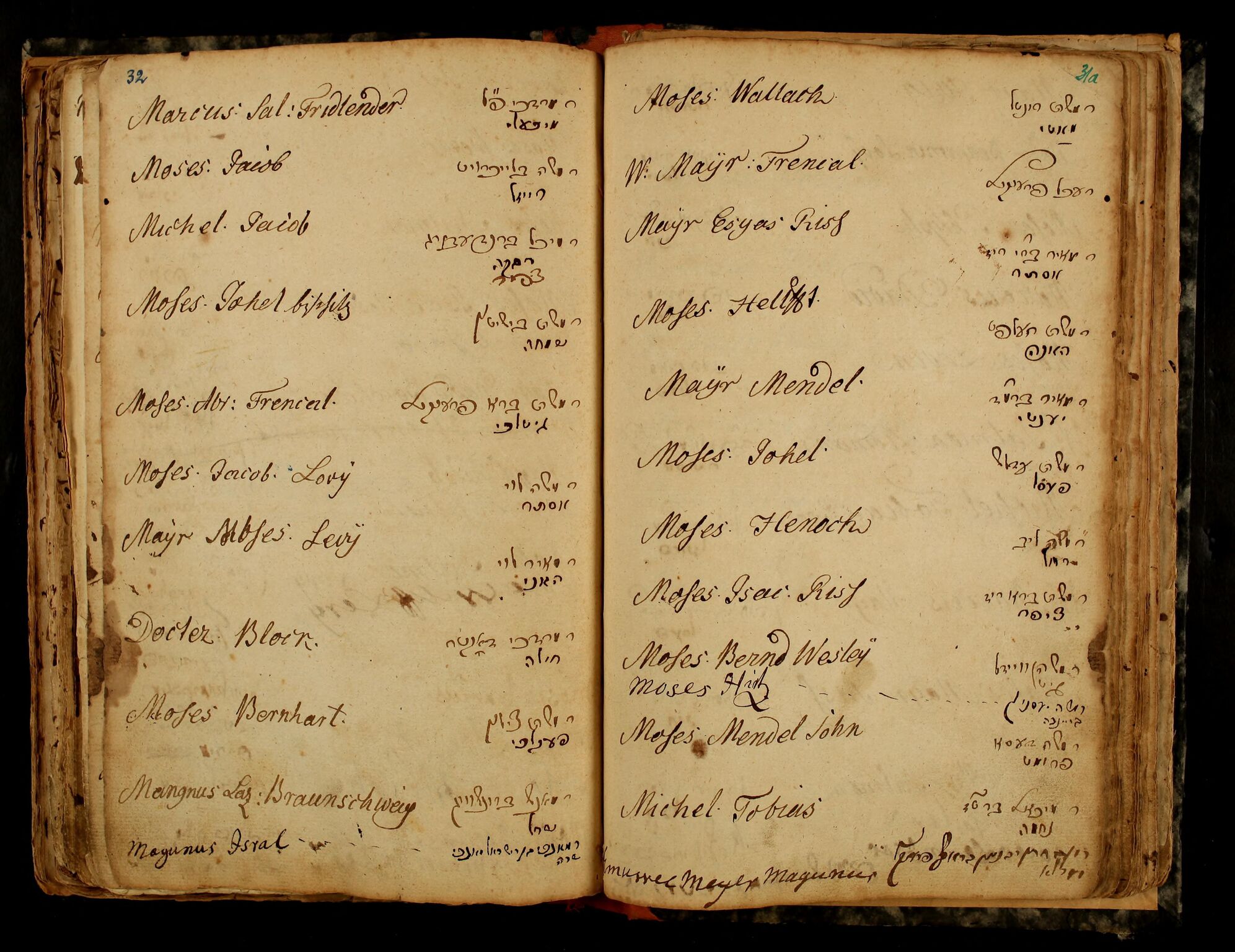

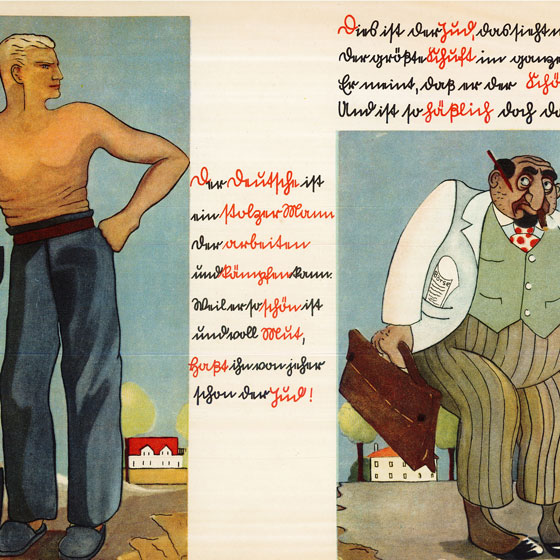

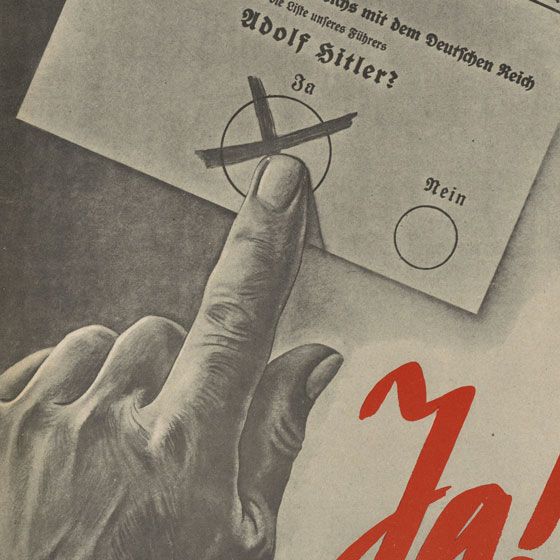

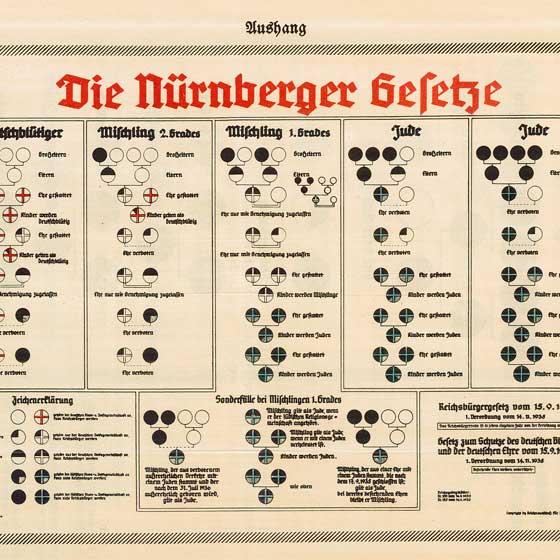

The Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin presents the year 1938 through the eyes of Jews, whose personal documents detail their experiences and the hardships they suffered as well as the growing tensions in Europe and diminishing hope for Jews in Germany and Austria.

Curated by Leo Baeck Institute – New York | Berlin

© 2018 Leo Baeck Institute

Website and exhibition design by C&G Partners