Inventing German-Jewish Children's Literature - Part 1

Teaching a German-Jewish Identity

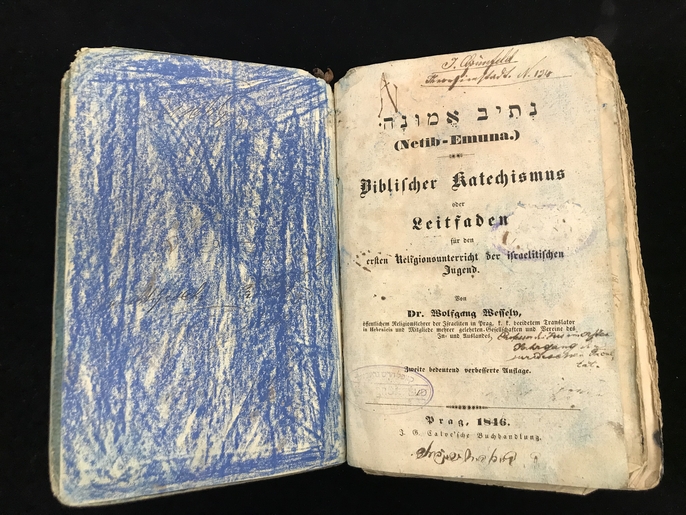

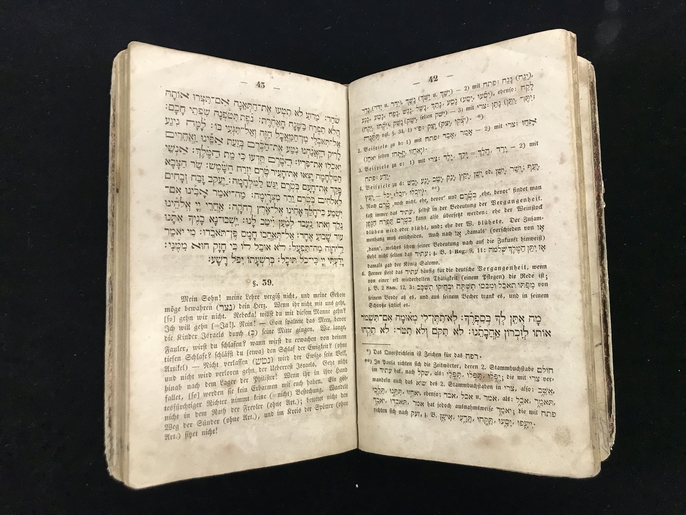

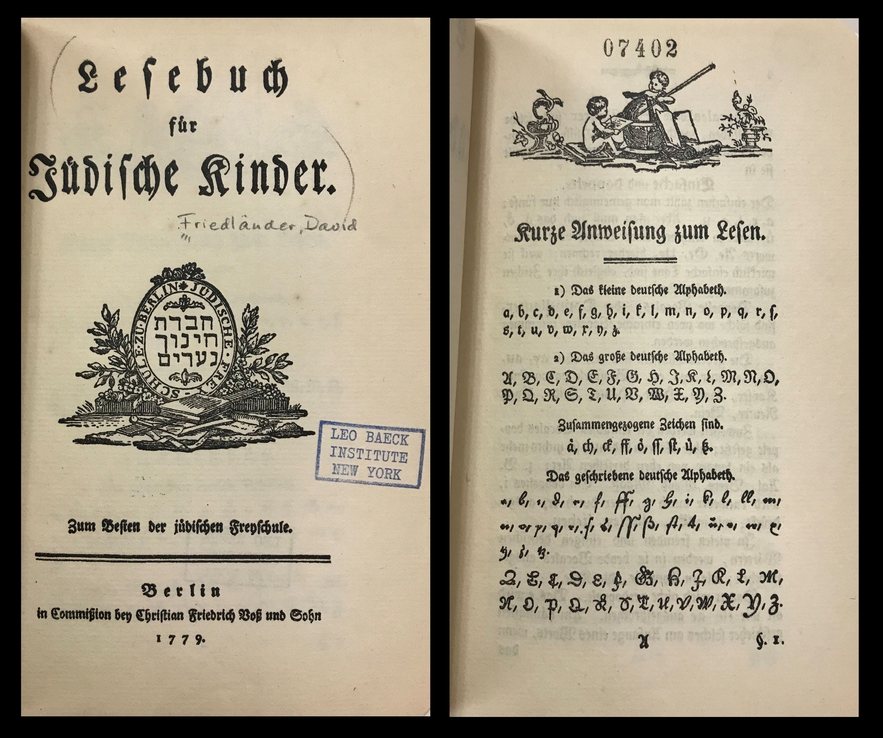

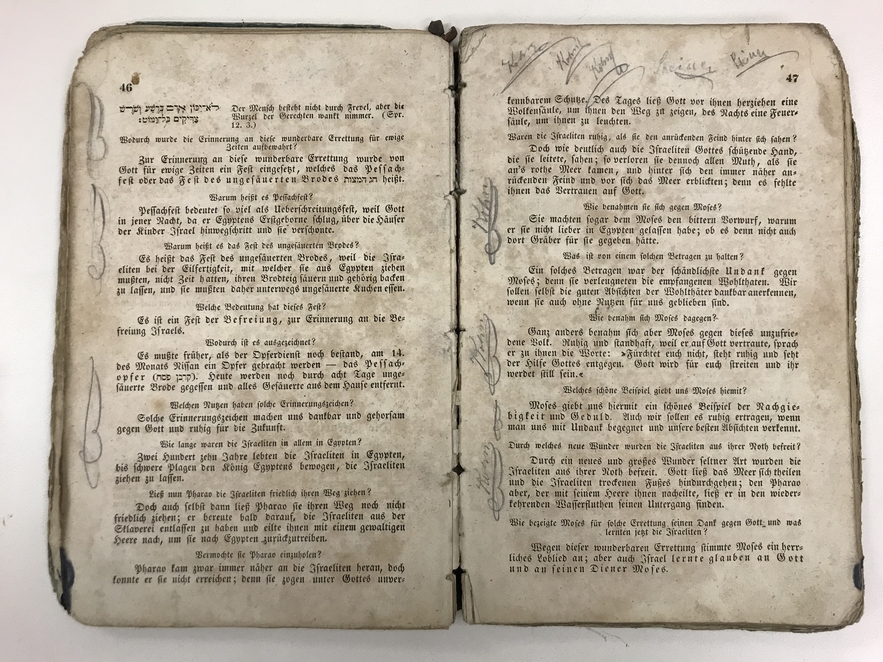

David Friedländer’s Lesebuch für jüdische Kinder (“Reader for Jewish children,” Berlin, 1779) was one of the first works that formed the idea of a German-Jewish childhood – a childhood rooted in both a German and Jewish identity. Published “zum besten der jüdischen Freyschule” (“for the benefit of the Jewish free public school”), Friedländer’s Lesebuch combined Enlightenment values with Jewish values, bringing Jewish education in line with the educational trends of their non-Jewish peers. Prior to the Freyschule, Jewish boys received a religious and not a secular education. Modernizing Jewish education was seen by Mendelssohn and other followers of Haskalah as a way bring about Jewish emancipation. This German-language textbook also represented a change in which Jewish writers began to write in German (rather than Hebrew) for Jewish children.

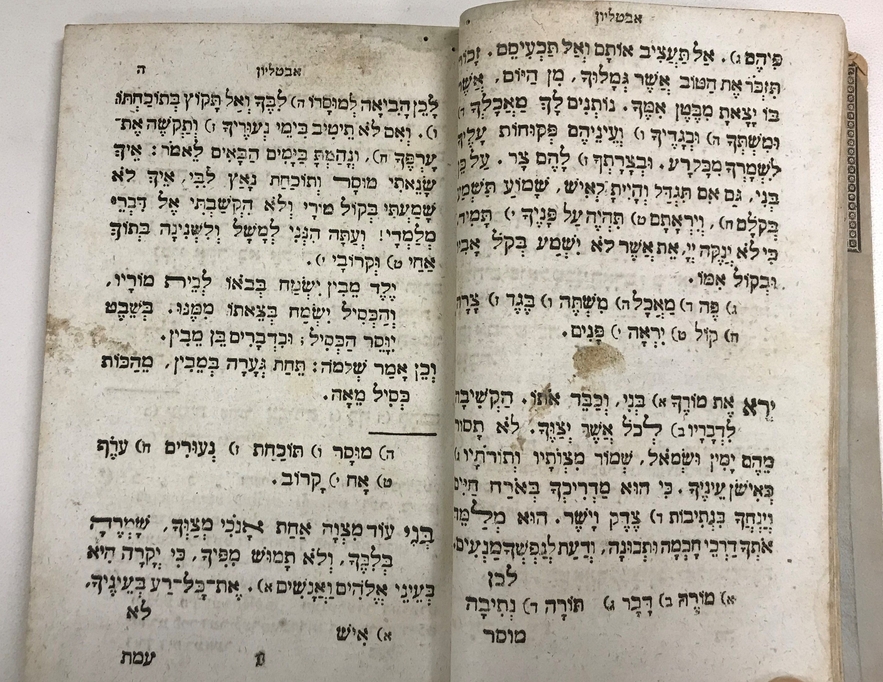

The Lesebuch für jüdische Kinder served as a model to non-Jews as well as Jewish parents of how a German and Jewish education could be combined. The textbook included elements of Judaism, such as Maimonides’s Principles of Faith, alongside examples of German letters, showing Jewish parents that the Enlightenment movement would not draw away from their faith. In a sense, Friedländer translated German culture into a Jewish culture, showing the Jewish community how to be enlightened Jews.

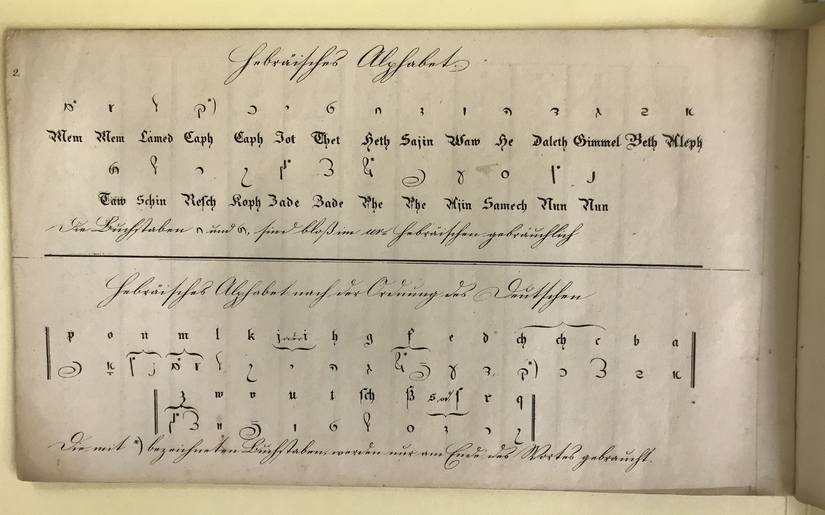

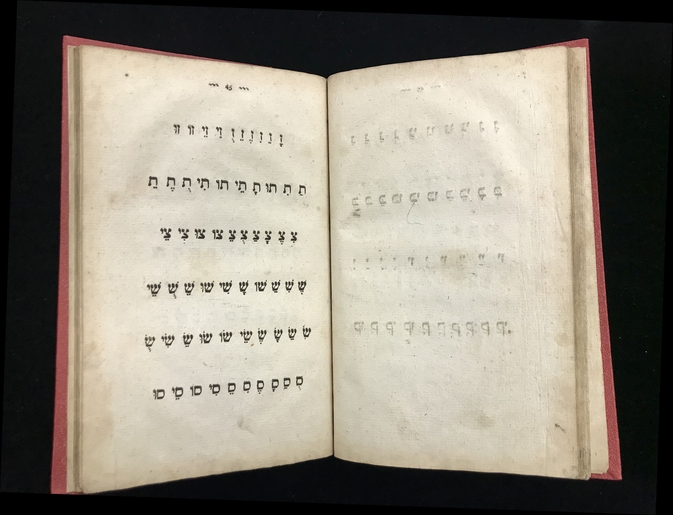

A significant feature of Friedländer’s textbook was its use of German as the primary language of instruction. The Haskalah movement sought to end the use of Yiddish. Both Mendelssohn and Friedländer associated Yiddish with unethical conduct and moral corruption. The first pages of the book showed reading exercises and rules for German pronunciation, as well as the alphabet in German letters. Its Jewish education – the principles of the Jewish faith, stories from the Talmud, Jewish fables – were all in German.

Although written for the Berlin Jewish Free School, it was not clear whether Friedländer's textbook was ever used by the school, or if it was simply intended to promote the school’s Enlightenment values. Opened in 1778, the Berlin Free School was as a blueprint for a number of similar Jewish Reform schools that followed in Breslau (1791), Dessau (1799), Seesen (1801), Frankfurt am Main (the famous Philanthropin, founded in 1804), and elsewhere.

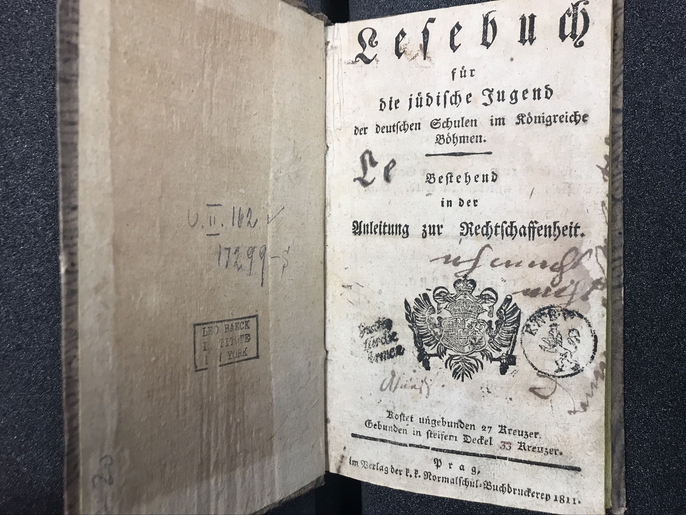

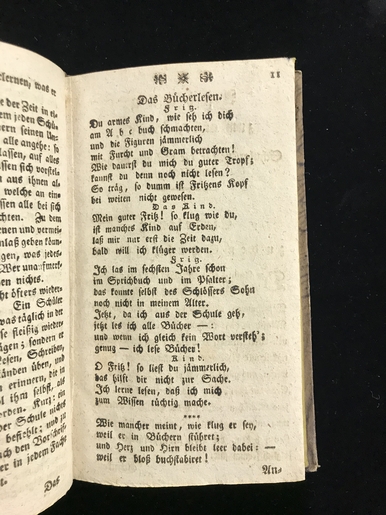

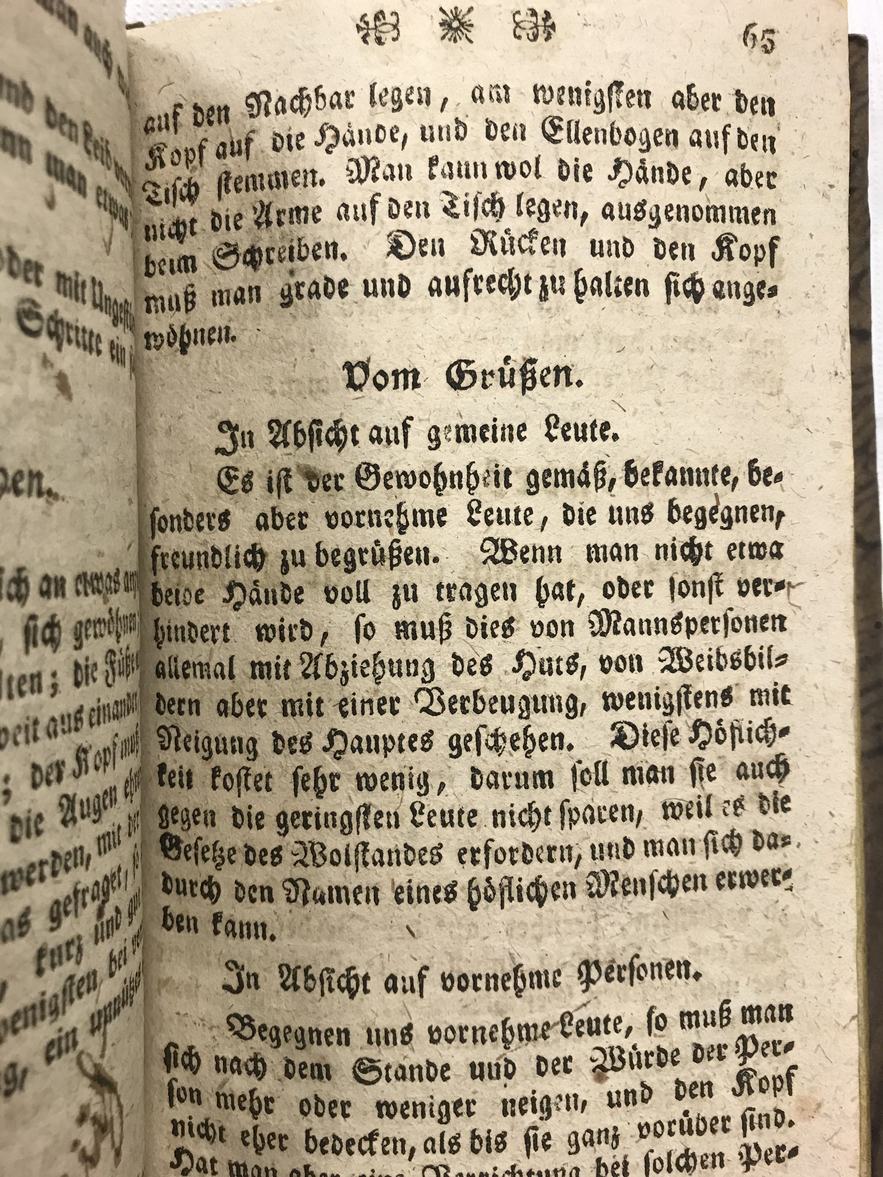

Another textbook for Jewish children, the Lesebuch für die jüdische Jugend der Deutschen Schulen im Königreiche Böhmen (“Reader for the Jewish youth in the German school in the Kingdom of Bohemia”) was probably intended more as promotional tool for the opening of the Prague Normalschule (Normal School) than as a school textbook. First published in 1781, a year before the opening of the Normalschule, its then-anonymous editor, Ferdinand Kindermann von Schulstein, was not a member of the Jewish community. Most of the text was taken from modern, non-Jewish textbooks with the Christian elements removed. Similar to Friedländer's Lesebuch, the book's emphasis on instilling social and moral values in Jewish students could be seen even in its title; the book was intended to provide an "Anleitung zur Rechtschaffenheit," a "guide to righteous living," encouraging Jewish children to abandon their uncouth behavior (a common prejudice against Jews) by teaching good manners and modest behavior.

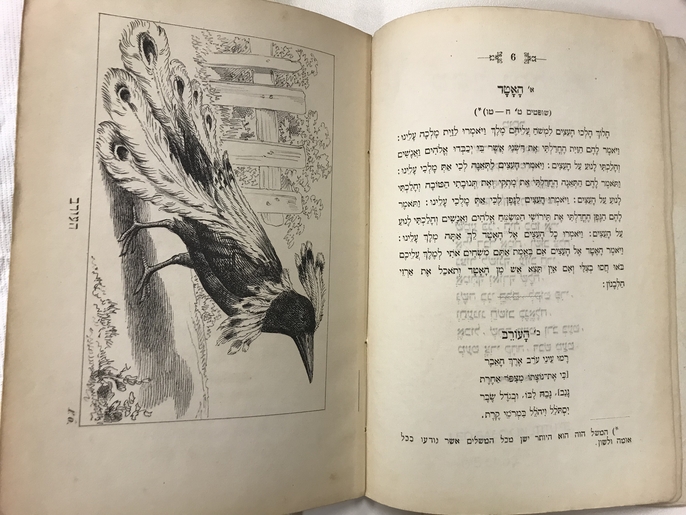

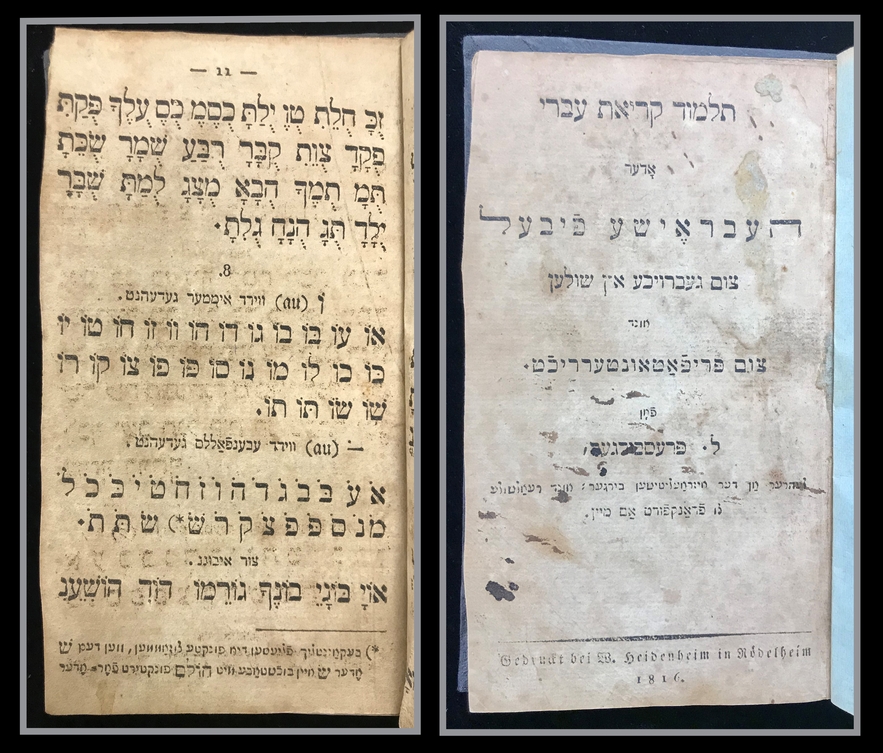

Hebrew children's literature printed during this time was influenced by the Haskalah. Parallel to publications in German, Hebrew children’s literature became a vehicle to convey Enlightenment values and was often didactic in nature. The first Hebrew texts for children were alphabet books and readers, then moral tales, fables, and some plays.

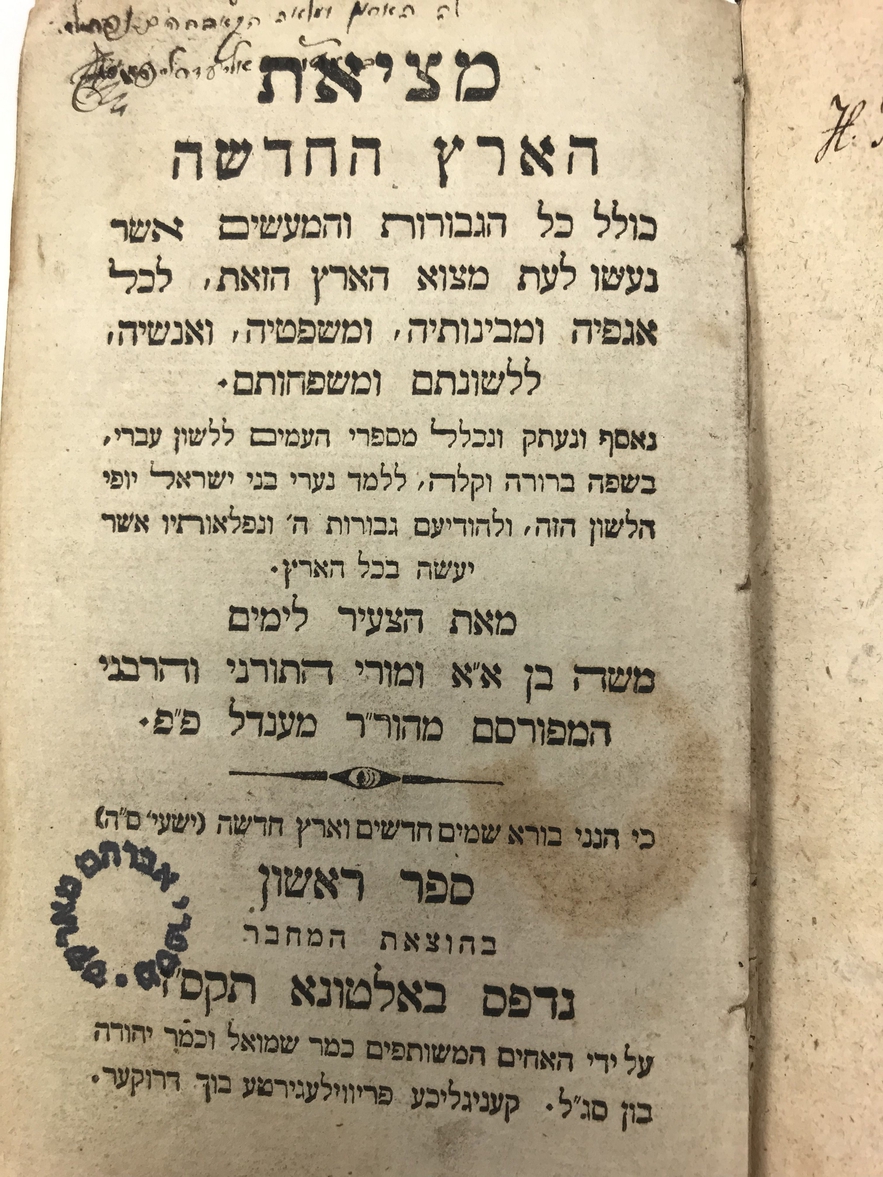

Writers considered to be models for the Enlightenment were often translated into Hebrew. Joachim Heinrich Campe was thought to be the most important German writer for children of the Enlightenment and thus he was the most frequently translated author into Hebrew. His books served as a model for other books written in Hebrew. Campe’s popularity and value to Hebrew literature may have been influenced by his friendship with Mendelssohn; the two corresponded and Campe had visited Mendelssohn in his home. Campe's book The Discovery of America was very popular among Enlightenment writers, possibly because it had potential to be an informational book of history and geography.

This new method of raising and educating children through a secular education of math, writing, languages, science, song, and exercise brought on integration. As Jewish children's education became more integrated, they were more likely to attend non-Jewish German schools. The German language was the most important subject, and over time all children were taught entirely in German - Hebrew and Yiddish were no longer a significant part of the curriculum.

Bibliography:

Shavit, Zohar, et al. Deutsch-Jüdische Kinder- und Jugendliteratur von der Haskala bis 1945. Stuttgart : J.B. Metzler, 1996.

Hinz, Renate and Wilhelm Topsch. "Jüdische Grundschulbücher aus drei Jahrhunderten." Jüdisches Kinderleben im Spiegel jüdischer Kinderbücher : eine Ausstellung der Universitätsbibliothek Oldenburg mit dem Kindheitsmuseum Marburg. Oldenburg, Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg, 1998. Pages 167-187.

Kaplan, Marion A. (editor). Jewish Daily Life in Germany, 1618-1945. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2005.

Kaplan, Marion A. The making of the Jewish middle class: women, family, and identity in Imperial Germany. New York : Oxford University Press, 1991.

Nagel, Michael. "The Beginnings of Jewish Children's Literature in High German: Three Schoolbooks from Berlin (1779), Prague (1781) and Dessau (1782)." The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book, Volume 44, Issue 1, (January 1999). Pages 39–54.

Schmitt, Hanoo. "Haskala und Philanthropismus : Begegnung und Austausch. " Jüdisches Kinderleben im Spiegel jüdischer Kinderbücher : eine Ausstellung der Universitätsbibliothek Oldenburg mit dem Kindheitsmuseum Marburg. Oldenburg, Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg, 1998. Pages 59-65.

Shavit, Zohar. "From Friedländer's Lesebuch to the Jewish Campe: The Beginning of Hebrew Children's Literature in Germany." The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book, Volume 33, Issue 1 (January 1988). Pages 385–415.

Shochat, Azriel, et al. "Haskalah." Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 8, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 434-444. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587508507/GVRL?u=new27191&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=aeff9f32. Accessed 7 Feb. 2022.