“Aufbau” – Reconstruction as a Mission

- Autor

- Andreas Mink

- Datum

- Fr., 1. Nov. 2013

Aufbau shuttered its New York offices in August 2004, but the paper’s story did not end there. The Swiss company JM Jüdische Medien AG acquired the paper and re-launched it as a monthly magazine a year later. JM Jüdische Medien’s US Editor, Andreas Mink, reflects on the history of the paper and its journey back to Europe.

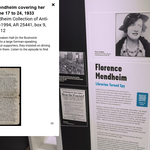

“Writing a history of Aufbau would mean telling the story of the German-Jewish immigration to New York and the tumultuous fates of the immigrants. But that story is neither fully formed nor finished,” wrote Manfred George in the summer of 1941. Georg was the Editor-in-Chief of Aufbau, a post he would hold until his death in 1965. After fleeing to the USA in 1939, George had joined Aufbau for a monthly salary of 15 dollars. Together with his colleagues, mostly former Berliners like him, including Hans Steinitz and Kurt Grossmann, George transformed the thin monthly newsletter of the New World Club into a weekly paper with a global impact.

In his long career, George had never witnessed “such an intimate link” between a publication and its readers as at Aufbau. He recalled “massive shipments” of letters to the editor and a never ending stream of visitors to the paper’s offices at Broadway and 74th St. on the Upper West Side. For its readers, the paper served as a “refuge, information bureau, missing person’s bureau, school, and news agency.” It was a classic example of the ways in which print media could function as a mouthpiece for specific political, ethnic, or social interests. However, Aufbau was more than all that. As George recognized, it was a medium for “resurrection on new ground, laying down new roots, and consolidating creative elements.”

As a forum for Jewish refugees from Hitler’s expanding German Reich, it helped to shape a common identity for Jews from all parts of the former Weimar Republic, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, who had previously been rooted in various regional cultures and milieus. This identity was based on more than Jewish tradition and the experience of persecution; it also included a “liberal and democratic attitude” in the American sense, according to a “Statement on Policy” for Aufbau and the New World Club that was adopted during World War II. Large-format photographic portraits of Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, and Franklin D. Roosevelt hung in the editorial offices as potent icons of this attitude and outlook. The chief precept enshrined in the “Statement” pledges the paper and the Club to aid the refugees’ integration into American society.

As we now know, this succeeded beyond all expectations. Take for example the careers of Harry Rosenfeld, Max Frankel, and Henry Grunwald, who rose to become leaders at the Washington Post, the New York Times, and Time Magazine, respectively. These journalists from the younger generation of refugees fulfilled Aufbau’s hopes; they became Americans and wrote in English but saw no need to abandon their heritage as German Jews. As a foreign-language niche publication, Aufbau, however, could not offer such young talent a future.

The integration of the younger generation precipitated a crisis of identity and purpose for the paper. Had it fulfilled its mission and made itself superfluous by helping the émigrés and their children become Americans? This was the subject of passionate debate in the editorial offices of the paper and the meetings of the New World Club in the 1990s. The answer was clear: German Jewish identity was an intellectual good and thus, in the spirit of the “Statement on Policy” cited above, had become the foundation of liberal, cosmopolitan, critical journalism. From this arose a duty for the Club and the editors of the paper to continue Aufbau for future generations.

The fact that this was not possible in Manhattan was due partly to the paper’s status as an independent publication of a non-profit organization. While George led the paper to editorial excellence, the editorial arm always lacked an equal counterpart on the business side—a competent, forward-looking publisher. The dedicated editorial team that modernized the paper’s content was not able to secure its future financially.

The Zürich-based JM Jüdische Medien AG was able to acquire Aufbau in summer 2004 and re-launch it as a monthly magazine in 2005, thanks in large part to the foundation and traditions established by the paper in New York. The new owner originated partly as the successor to the Jüdische Rundschau, which had been moved to Switzerland during the Nazi era, and thus had a broad intellectual affinity with Aufbau. Today, die JM Jüdische Medien AG functions as a service provider for Aufbau’s publisher, the Serenada Verlag. This combination offers the stability and publishing competence that has allowed the new Aufbau to grow for nine years.

With this organizational basis, the small editorial team at Aufbau draws inspiration from the paper’s tradition to tackle a broad spectrum of social, political, cultural, scientific, and religious issues. The US remains an area of focus alongside Europe, Israel and other regions. The paper’s supporters include not only prominent Jewish authors like Robert Menasse, Walter Laqueur, Elie Wiesel and Jared Diamond, but non-Jews such as Al Gore.

ONLINE:

Andreas Mink is the US editor for JM Jüdische Medien AG, which has published Aufbau as a monthly magazine in Zurich since 2005. He also worked as a journalist for the New York Aufbau for many years.

Aktuelles