New Exhibit to Explore Life in Theresienstadt

- Datum

- Di., 1. Mär. 2022

In his landmark study of Theresienstadt, H.G. Adler characterized the transit camp about 60 kilometers northwest of Prague as a Zwangsgemeinschaft – a coerced community. For tens of thousands of German, Austrian, and Czech Jews, it was a way station on the road to destruction; fewer than 6,000 survived the malnutrition, rampant typhus epidemics, and transports to death and labor camps. The first transports of Jews from Germany arrived in June, 1942, after the murder of European Jews had become official Nazi policy. Though Theresienstadt was notoriously instrumentalized as a “model ghetto” for propaganda purposes, it was always part of the machinery of the Final Solution.

Like other prisons, however, it was a place with its own distinct social life – a community – albeit one that grew within the convoluted framework dictated by the SS. In Theresienstadt, that framework perversely afforded the Jewish administration great autonomy in running the day-to-day affairs of a small town, but that autonomy was always subsidiary to the end goal of destroying the town’s people and their culture. This circumstance produced the two characteristics that have come to dominate the popular understanding of Theresienstadt. On the one hand, the efforts to serve the population’s spiritual needs produced an astonishing level of cultural activity, from the lectures of Leo Baeck, to the performances of Verdi’s Requiem. At the same time, the administration was forced to preside over the transports to death camps, actions which later became fuel for the admonitions of collaboration by later observers like Hannah Arendt.

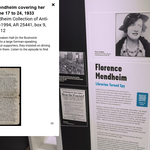

Both the high level of cultural production and the highly bureaucratic Jewish administration of the camp mean that there is rich documentation of life in the camp. The LBI’s archival and art collections include records and ephemera kept by survivors or retrieved after liberation as well as memoirs and personal papers documenting the lives of internees before and after Theresienstadt. These range from the papers of Else Oestreicher, an author of cookbooks who worked in the Theresienstadt kitchen, to the papers of Leo Baeck himself. Although photography was prohibited in Theresienstadt (with the exception of the infamous propaganda films), artists working in the technical and drawings department such as Norbert Troller, Leo Haas, and Charlotta Burešová recorded what they saw – both officially, for the eyes of the SS, and secretly, to reflect the reality of their experience.

This exhibit focuses on the stories of individuals – their lives, and often deaths – in Theresienstadt.

From LBI News 113

Aktuelles