Shira Klein: Teaching Research Skills with DigiBaeck

- Author

- David Brown

- Date

- Fri, Nov 1, 2013

With the launch of LBI’s digital archive, historian Shira Klein immediately recognized a new tool for engaging undergraduates in original research using primary sources. We asked her about her experience using DigiBaeck in the classroom.

What was the topic of your course?

It was a history course called “History of Jewish Migration,” and we looked at a different chapter of Jewish migration every week, from the Babylonian captivity to the emigration of Iraqi Jews in the 1950s. We focused on Jewish migrations, but we examined them based on the factors that impact every migration: push and pull factors, issues of identity before and after arrival, the impact on different genders, ages, and social classes, etc.

The final project was a research paper about the Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany and Austria in the 1930s. Students had to cite secondary literature as well as primary sources found through DigiBaeck.

How did you introduce the concept of working with primary sources?

Every week I paired a secondary source with a primary source and asked the students to analyze them in response papers based on a prompt I provided. The goal was for them to state how an argument articulated in a secondary source is reinforced or called-into question by a primary source.

The research paper was like the response papers, except the students had to develop their own “prompt” and argument as well as find their own primary sources.

So, the students started working with primary sources that you spoon-fed to them, and then they had the opportunity to experience the work a historian does to track down original materials.

That’s why an online archive like DigiBaeck is so terrific. The students actually told me they couldn’t believe how difficult it was to find a primary source that supported the argument they wanted to make.

Of course, history doesn’t work that way. Searching in an archive on their own helped the students develop an appreciation for how complicated history is and how careful historians need to be with sources when crafting a historical argument.

What kinds of documents did the students use?

They primarily relied on memoirs, which were well-suited to this project. First, many of the memoirs were written in English or later translated, while original documents and correspondence were mostly in German. There are over 2,000 memoirs in DigiBaeck, so there were plenty to choose from.

The other great thing about memoirs as historical documents is that they can cover the key events of a period of years or decades, while contemporary documents, like letters, typically only relate to the events of days or weeks. So, you can cover 10 years in ten pages of a memoir, or get the events of August 4, 1936, in a letter.

Was it difficult to get the students to view these materials critically?

We had practiced that in the response papers. Throughout the term, some of the primary sources we examined were in conflict with what I was teaching. We looked at them and asked, “What’s wrong here? Is this representative, or reliable?” Conversely, we might discuss a popular view on a given topic, and then use the primary source to question that view.

They applied the same methods in their research papers. For example, one of the arguments we discussed in the course was that Jews who emigrated from Eastern Europe to Palestine in the early 20th century were motivated less by Zionism than by the same factors that led others to go to the United States or South America—namely, social and economic hardships.

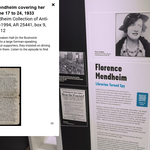

One student focused on this very argument, but in the context of German-speaking refugees in the 1930s. The student used a number of oral history interviews from the Austrian Heritage Collection. The interviewees explained their decision to go to Palestine as motivated by ardent Zionist sentiment. Rather than take this explanation at face value, the student made a careful study of the push and pull factors that had led the interviewees to leave Germany and found that it was social and economic persecution first and foremost that led them to leave.

How did the course challenge the students’ assumptions?

Some assumed that all Jews must have wanted to leave Germany immediately when Hitler came to power. One of the primary sources we studied before the research project was “Proclamation by the Central Committee of German Jews for Relief and Reconstruction,” published in the CV-Zeitung. In April 1933, even after the Nazis were in power and some persecution had already begun, the German-Jewish leadership issued this statement saying, “Do not imagine that the problems of German Jewry can be solved… by means of… emigration. There is no honor in leaving Germany… Do your duty here.” It also calls Germany “the German Fatherland.”

We used this document both to show that not everyone automatically wanted to leave immediately after Hitler came to power—as students sometimes assume was the case—and to show that German Jews felt very connected to Germany.

ONLINE:

Latest News